Whether you want to buy an existing business or start your own, your first move must be to do as much market research as possible, and this should include the level of potential competition for your business, both from other small traders and from any nearby large chain stores or supermarkets – and you should check at the town hall or mairie whether there are plans to build new shops in the area. If it’s an area that you’re unfamiliar with in commercial terms, start by spending as much time as you can in and around your intended location watching the flow of people. Talk to as many people as you can and ask as many questions as you dare – of expatriate and of French consumers – to find out the needs and buying habits of the locals and, if relevant, tourists, in order to get a feel for the potential demand for your product or services.

Licences & Permissions

It’s important to be clear about your needs and to find out what the regulations are before you commit yourself to any particular premises. If they don’t meet the requirements, it could be a complicated and expensive business to bring them up to scratch. Although no general licence is required to set up a shop or retail business, different regulations apply to different types of operation. If you intend to sell alcohol or tobacco products, for example, strict rules and procedures apply.

If you want to sell from a market stall (known as an activité non-sédentaire), you will need a carte de commerçant ambulant from your local préfecture as well as all the usual registration documents. The card needs to be revalidated every two years and renewed after ten. To secure a ‘pitch’ in a market, you must apply to the relevant town hall for a permis d’occupation du domaine public. Further information about operating as a market trader can be obtained from the Fédération Nationale des Syndicats des Commerçants des Marchés de France (www.fnscmf.com ).

Seek advice from a lawyer or a notaire about the requirements for your particular business and remember that they may vary from one region or department and even one commune to another.

Shopfitters & Suppliers

It isn’t easy to find English-speaking shopfitters in France, although the UK National Association of Shopfitters has a list of members who operate internationally on its website (www.shopfitters.org ). This may be a more expensive option than using a French company or artisans, which may therefore be preferable if your French is more fluent.

However, as shopfitting isn’t a recognised trade in France (there isn’t even a word for it!), you may have difficulty finding a single company that can fit out your shop entirely. Instead, you may need to use several specialist tradesmen, such as a plasterer, an electrician, a plumber, a carpenter, and so on. This can work out expensive, especially if you cannot be on site (or don’t have good enough French) to coordinate the work yourself and need to engage an architect or maître d’oeuvre (‘clerk of works’) to do so on your behalf. As with any service in France, it’s best to seek recommendations.

Where you source your stock obviously depends on the type of shop you plan to run. If you must buy abroad, e.g. in the UK, you may need to use an intermediary, such as a distributor or wholesaler.

Insurance

Insurance is a vital consideration if you don’t want to lose everything you’ve worked for. You need buildings insurance against obvious risks such as fire and water damage. If you rent the property from a landlord, he should already have this, but you should check the details of the policy before you sign your rental contract. Then there are the contents of shop, the fixtures and fittings and your stock, which need insuring against damage and theft, including when stock is in transit. You must also ensure that you have sufficient public liability insurance, which means that should any customer injure himself in your shop and claim against you, your insurance company will pay (unless you’ve been negligent). If you employ others, you also need employer’s liability insurance and to pay social security contributions on behalf of your staff so that they’re covered for accidents, illness, etc. Ask around for a reliable broker or insurance agent, as there are plenty of companies offering insurance to businesses, some in specific business sectors.

Marketing

Look carefully at all the publications you can, talk to other businesses that advertise in them and ask about their success rate. You can spend a large proportion of your advertising budget on a glossy magazine advertisement only to find that you get little or no custom from it. Besides, the French in particular almost always prefer to have a recommendation and rarely contact a business ‘cold’ from an advertisement.

Once you’re a little more established, your marketing needs will become clearer and you will be able to be more discerning about how you spend your money. In this sense, running a retailing business in France is no different from running one anywhere else: you can never afford to rest on your laurels.

Information on different kinds of retails

As in most western countries, the vast majority of people wear casual clothes (jeans, trainers, sweatshirts, etc.) 90 per cent of the time (except when sleeping), and ‘logo mania’ is as prevalent as in the UK or US. Nevertheless, it’s still true that the French value quality, and you may be more successful with an upmarket clothes shop than in many other countries, provided you choose the location carefully. Would-be shopkeepers should also note that it isn’t usual to open on Sundays and most shops are also closed on Mondays. Sale periods in France are strictly limited by law (a maximum of a month in July/August and a month in January/February)

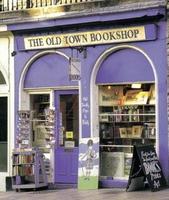

The French are avid readers and generally prefer to buy books than borrow them from libraries (France has no second-hand ‘culture’, and libraries are rarely found outside main towns). Nevertheless, books are expensive, there may be only one book shop in even a fairly large town. Many expatriates have set up English-language book shops, although these are necessarily restricted to areas where there’s a large expatriate population or major cities (there’s just one in Rouen, a city of half a million people, for example).

Needless to say, any business connected with computing or IT requires not only a detailed understanding of the relevant technology, but also knowledge of the specialist French terminology, although much of it is ‘borrowed’ from English. Although computing and telecommunications technology is more or less the same the world over, there are inevitably a certain number of French ‘idiosyncrasies’. To take an obvious example, French computer keyboards have a different arrangement of keys from English-language keyboards (AZERTY instead of QWERTY).

Before setting up a food or drink retailing operation in France, you must study the types of food and drink outlets that are common in France. To give two obvious examples: there are few ‘off-licences’ in France, where most drinks are bought from supermarkets and hypermarkets. You must also make a detailed study of French eating and drinking habits as these may be quite different from those in your home country. Again, to give two obvious examples: the French generally don’t drink non-French wine, and few French people are vegetarian. Beyond this, you must make yourself aware of current trends in eating and drinking habits. For example, the French are generally eating less ‘red’ meat and more ‘white’ meat than they used to; they’re also buying more and more packaged and frozen food, so that specialist food shops are finding it harder to survive. On the other hand, ‘health’ and diet foods are becoming more popular, and there are, as yet, few dedicated ‘health food shops’ compared with the UK, for example. Perhaps the first food retailing idea that springs to the minds of expatriates is selling foreign foods that aren’t readily available in France. To be successful, such an operation obviously requires a large expatriate population, and even then it may be wise to combine the food with other products; it’s unlikely that you will win many French customers.

This article is an extract from Making a living in France.

Click here to get a copy now.